The Rivesaltes Camp witnessed three major conflicts that France, Europe and North Africa experienced in the space of just three decades: the Spanish Civil War, the Second World War and the Algerian War.

During this time, the barracks of Rivesaltes Camp saw thousands of men, women and children of different origins and nationalities pass through. The internment of these population groups at the Rivesaltes Camp is an example of the forced displacements resulting from these conflicts and from the decolonisation movements that rocked the 20th century.

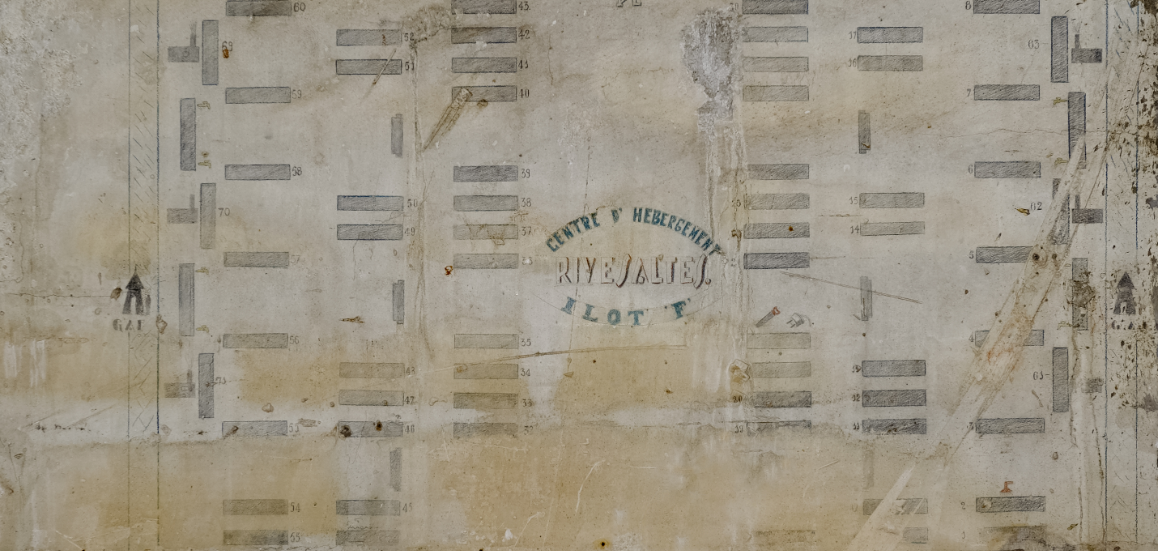

Initially built to be a military training camp, Rivesaltes was also used, among other things, as an accommodation centre for undesirable foreigners, an internment camp for population groups targeted by the exclusion policies of the Vichy regime, a transit camp for deportation to Auschwitz-Birkenau via Drancy, a camp for German prisoners of war, a centre for foreign colonial auxiliaries of the French army, and a “rehabilitation” camp for Harkis and their families. Its history is that of the Spanish Republicans, foreign Jews, gypsies, POWs of the Axis powers, Harkis, prisoners of the Algerian National Liberation Front (FLN), Guineans, North Vietnamese and all those who stayed there in often very harsh conditions.

A camp intended for the military

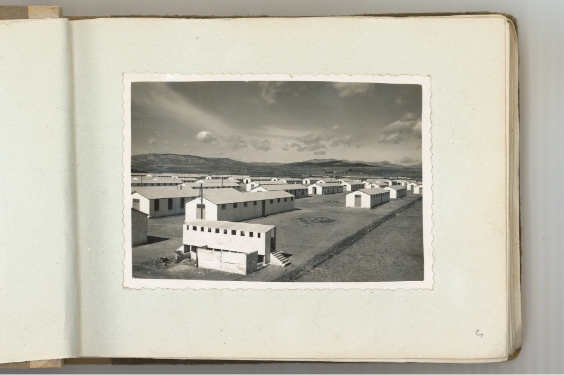

The Rivesaltes plains and their vast expanse of heathland was scouted in 1923 by the military authorities as an ideal site for military and firearms training

Although the idea to build a military base in Rivesaltes dated back to the interwar period, Camp Joffre (named after General Joffre, a native of the town of Rivesaltes) did not see the light of day until the beginning of the Second World War. As such, in 1939, the still uncompleted Rivesaltes Camp was used to house small groups of colonial indigenous people in transit, while other makeshift camps sprung up in the region to house Spanish Republicans who fled as part of the exodus that came to be known as La Retirada.

In the autumn of 1940, the French Minister of War transferred the management of the internment camps to the Ministry of Internal Affairs. The former sought to relieve tension from the camps in Argelès-sur-Mer, Saint-Cyprien and Gurs. Accordingly, in late 1940, nine blocks of the Rivesaltes Camp were assigned to the Ministry of Internal Affairs in order to create an accommodation centre. The first convoy of internees arrived on 14 January 1941.

The military function of the Rivesaltes Camp was partly determined by the Second World War and the different stages of the conflict: declaration of war and mobilisation, the Phoney War and the Battle of France, the armistice and demobilisation of the French army under the Vichy regime, the invasion of Southern France by German troops and, finally, the departure of the German troops and the Liberation. The camp would continue to have a military function, on and off, throughout the entire period it was in operation, leaving the traces of a complex history on its 612 hectares.

Administrative internment and a turn for the worse

The French decree for the administrative internment of “undesirable foreigners” of 12 November 1938 established in law the administrative detention of people who were likely to represent a “potential danger” to France.

At the time this law was passed, it was intended to mainly target refugees from Nazi Germany and Central and Eastern Europe. The first detention camp to open was the Rieucros Camp in Lozère in January 1939. However, very soon after, it was used in order to accommodate thousands of Spanish Republicans and civilians fleeing the Spanish Civil War, after the fall of the Northern Front, which was an entirely unexpected development for the French government. Within a context of pronounced xenophobia, the response to the arrival of 450,000 Spaniards, who mostly first set up camp on the beaches in Roussillon, Argelès-sur-Mer, Saint-Cyprien and Barcarès, was to construct thirty or so internment camps.

The establishment of the authoritarian Vichy regime in July 1940 made the policy for the exclusion of undesirable foreigners widespread, as well as institutionalising antisemitism. Within the space of a few months, over 50,000 people found themselves taken to these camps in Southern France.

The Rivesaltes accommodation centre was officially opened on 14 January 1941. The Spanish internees were accompanied by foreign Jews and French gypsies, who were evacuated from Alsace-Moselle as a result of the travelling restrictions targeting nomads. The health conditions and lack of basic supplies made life in the camp very hard. Thousands of foreign Jews arrived in Rivesaltes in 1942 when the camp became an Inter-Regional Accommodation Centre for Israelis, known as the “Drancy of the South”. The camp played a key role in France’s collaboration policy by rounding up foreign Jews and deporting them to Auschwitz.

Of the 5,000 Jewish internees at Rivesaltes, 2,289 men, women and children would be sent away in nine different convoys between 11 August 1942 and November 1942. However, over half would escape the fate of these convoys thanks to the work of humanitarian organisations (the Swiss Red Cross, OSE, Cimade, YMCA, Unitarian Service, etc.), as well as thanks to the efforts of Paul Corazzi, the Prefect representative. In less than two years, 17,500 people would be interned at Rivesaltes, of whom 53% were Spaniards, 40% were foreign Jews and 7% were French gypsies.

German occupation and Liberation

On 22 November 1942, around ten days after the German occupation of the south, the German troops emptied the camp in order for it to fulfil its original purpose: a base for the troops entrusted with defending the coasts. The remaining internees were taken to other camps, such as Gurs and Saliers, or transferred to so-called Foreign Worker Groups.

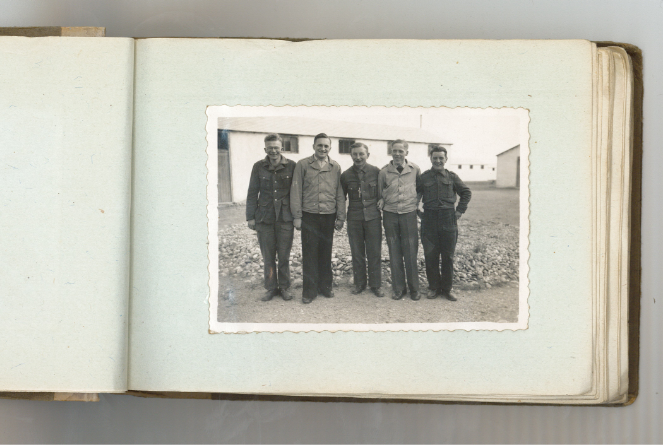

Following the Liberation, the Rivesaltes Camp became a surveillance residence centre for people suspected of collaborationism (1944-1945) and a depot for prisoners-of-war of the Axis powers (1944-1948). This included Germans, Austrians, Italians and Hungarians, along with Spaniards and Soviets. Many detainees were sent to perform work in the region until their release.

From the Algerian War to the mass arrival of Harkis

During this period, the Algerian War would leave its mark on the history of the Rivesaltes Camp. Many recruits headed for Algeria would stay at the camp before embarking at Port-Vendres for their journey across the Mediterranean.

Between January and May 1962, part of the Rivesaltes Camp also regained its post-war role as a prison with the opening of a prison camp for militants and supporters of the Algerian National Liberation Front (FLN).

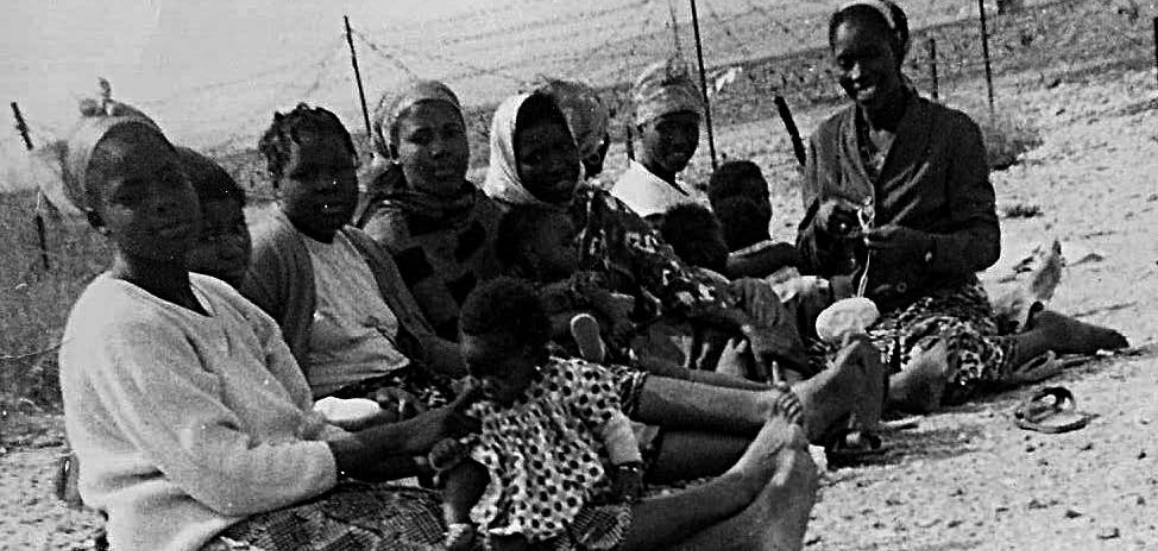

At the end of the war, four blocks were turned into a prison for Algerian nationalists from the National Liberation Front (FLN). However, in September 1962, a few months after the signing of the Évian Accords, the former colonial auxiliaries of the French Army in Algeria, known as the Harkis, arrived. The Rivesaltes Camp thus became the Accommodation Centre for French People of North-African Descent (FSNA in French). Those who were able to leave Algeria with their families were brought here, often from other relegation centres such as Bias, Bourg-Lastic and Larzac. Faced with overcrowding and run-down barracks, the families found themselves first lodged in military tents. On top of the shortage of supplies and overcrowding, there was psychological distress and the pain of exile. The harsh wind and cold of the winter of 1962 only worsened the already precarious living conditions. With the transfer of families to the barracks, life gradually became better organised. However, the integration of the former colonial auxiliaries and their families was difficult. Rejected by newly independent Algeria, by part of French society and by those that rejected them as Arabs, they remained marginalised by the French government for a long time.

Many of them were urged to go to work in the mines and the steel industry in Northern France. Others were sent over time to housing developments in urban areas specially designed to accommodate them, or to 75 forest villages located mainly in the south and southeast of France (one of which was at the Rivesaltes Camp).

The Rivesaltes transit camp officially closed in December 1964, having accommodated 21,000 Harkis and their families. A temporary so-called civil village continued to exist until March 1965. The last families to leave the Rivesaltes forest village were relocated in the Réart government-subsidised housing complex in the village of Rivesaltes in 1977.

From decolonisation to the new undesirables

After the Harkis left and until March 1966, the camp barracks were used to house Guinean soldiers fighting for France, along with their families. In total, France sent around 800 men, women and children to Rivesaltes Camp. At this time, the camp also accommodated a small group of soldiers from North Vietnam, who had arrived from Indochina.

The camp once again became a military establishment. Another phase in the camp’s history was between 1986 and 2007, when one of the blocks was used as a small administrative detention centre for foreigners eligible for deportation. This centre was finally transferred in November 2007.